Reprinted from

History and Women Blog.

In Ancient Rome, the vestal virgins were virgin female priestesses of Vesta, the goddess of the hearth. It was their job to maintain the sacred fire of Vesta.

This duty was a great great honor and granted the women many privileges and honors. They were the only female priests within the Roman religious system.

The discovery of a "House of the Vestals" in Pompeii made the vestal virgins a popular subject in the 18th century and the 19th century. The objects of the cult were essentially the hearth fire and pure water drawn into a clay vase.

A Roman man by the name of Numa Pompilius introduced the vestal virgins and assigned them salaries from the public treasury.

He stole the first vestal virgin from her parents. More vestal virgins were added later. The women became a powerful and influential force in the Roman state.

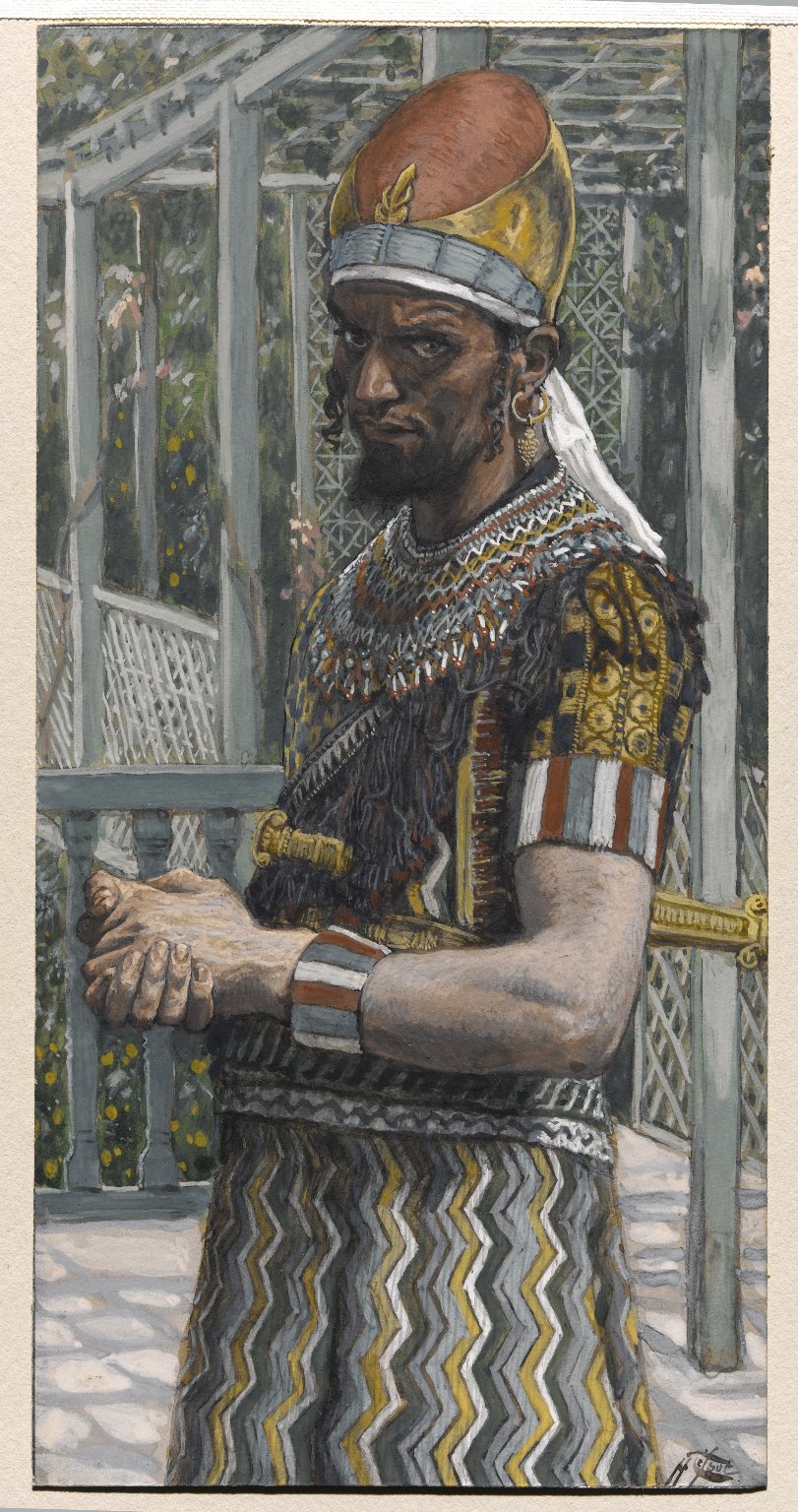

Numa Pompillius

The chief vestal oversaw the efforts of the vestals. The last known chief vestal was Coelia Concordia in 380. The College of Vestal Virgins ended in 394, when the fire was extinguished and the vestal virgins disbanded by order of Theodosius I.

The vestal virgins were committed to the priesthood at a young age (before puberty) and were sworn to celibacy for a period of 30 years. These 30 years were, in turn, divided into three periods of a decade each: ten as students, ten in service, and ten as teachers. Afterwards, they could marry if they chose to do so.

However, few took the opportunity to leave their respected role cause they lived luxuriously and marriage would have required them to submit to the authority of a man, with all the restrictions placed on women by Roman law. On the other hand, a marriage to a former vestal virgin was highly honoured.

A vestal was chosen by the high priest from young girl candidates between their sixth and tenth year. To obtain entry into the order they were required to be free of physical and mental defects, have two living parents and to be a daughter of a free born resident in Italy.

To replace a vestal who had died, candidates would be presented in the quarters of the chief vestal for the selection of the most virtuous. Once chosen they left the house of their father, were inducted by the pontifex maximus, and their hair was shorn. The high priest pointed to his choice with the words, "I take you to be a vestal priestess, who will carry out sacred rites which it is the law for a vestal priestess to perform on behalf of the Roman people, on the same terms as her who was a vestal on the best terms".

Their tasks included the maintenance of the fire sacred to Vesta, the goddess of the hearth and home, collecting water from a sacred spring, preparation of food used in rituals and caring for sacred objects in the temple's sanctuary. By maintaining Vesta's sacred fire, from which anyone could receive fire for household use, they functioned as "surrogate housekeepers", in a religious sense, for all of Rome. Their sacred fire was treated, in Imperial times, as the emperor's household fire.

The vestals were put in charge of keeping safe the wills and testaments of various people such as Caesar and Mark Antony. In addition, the vestals also guarded some sacred objects, including the Palladium, and made a special kind of flour called mola salsa which was sprinkled on all public offerings to a god.

The dignities accorded to the vestals were significant. In an era when religion was rich in pageantry, the presence of the Vestal Virgins was required in numerous public ceremonies.

They travelled in a carpentum, a covered two-wheeled carriage, preceded by a lictor, and had the right-of-way. At public games and performances they had a reserved place of honor. Unlike most Roman women, they were free to own property, make a will, and vote. They gave evidence without the customary oath. They were, on account of their incorruptible character, entrusted with important wills and state documents, like public treaties. Their person was sacrosanct. Death was the penalty for injuring their person and their escorts protected anyone from assault. They could free condemned prisoners and slaves by touching them - if a person who was sentenced to death saw a vestal virgin on his way to the execution, he was automatically pardoned. They were allowed to throw ritual straw figurines called Argei, into the Tiber on May 15 celebrations.

Site of the House of Vestal Virgins in Rome

Allowing the sacred fire of Vesta to die out, suggesting that the goddess had withdrawn her protection from the city, was a serious offense and was punishable by scourging.

The chastity of the vestal virgins was considered to have a direct bearing on the health of the Roman state. When they became vestal virgins they left behind the authority of their fathers and became daughters of the state. Any sexual relationship with a citizen was therefore considered to be incest and an act of treason. The punishment for violating the oath of celibacy was to be buried alive in the Campus Sceleratus or "Evil Fields" (an underground chamber near the Colline gate) with a few days of food and water.

Ancient tradition required that a disobedient vestal virgin be buried within the city, that being the only way to kill her without spilling her blood, which was forbidden. However, this practice contradicted the Roman law, that no person may be buried within the city. To solve this problem, the Romans buried the offending priestess with a nominal quantity of food and other provisions, not to prolong her punishment, but so that the vestal would not technically die in the city, but instead descend into a "habitable room". Moreover, she would die willingly. Cases of unchastity and its punishment were rare. The vestal Tuccia was accused of fornication, but she carried water in a sieve to prove her chastity.

Vestal sentenced to die

Because a vestal's virginity was thought to be directly correlated to the sacred burning of the fire, if the fire were extinguished it might be assumed that either the vestal had acted wrongly or that the vestal had simply neglected her duties. The final decision was the responsibility of the pontifex maximus, or the head of the pontifical college, as opposed to a judicial body.

While the order of the vestal virgins was in existence for over one thousand years there are only ten recorded convictions for unchastity. The earliest vestals were said to have been whipped to death for having sex.

The paramour of a guilty vestal was whipped to death in the Forum Boarium or on the Comitium.

The chief festivals of Vesta were the Vestalia celebrated June 7 until June 15. On June 7 only, her sanctuary (which normally no one except her priestesses, the vestal virgins, entered) was accessible to mothers of families who brought plates of food. The simple ceremonies were officiated by the vestals and they gathered grain and fashioned salty cakes for the festival. This was the only time when they themselves made the mola salsa, for this was the holiest time for Vesta, and it had to be made perfectly and correctly, as it was used in all public sacrifices.

Vestals wore an infula, a suffibulum and a palla. The infula was a long headdress that draped over the shoulders. Usually found underneath were red and white woolen ribbons. The suffibulum was the brooch that clipped the palla together. The palla was a simple mantle, wrapped around the vestal virgin. The brooch and mantle were draped over the left shoulder.

Learn more about women and their fascinating bios and histories at

History and Women